Truly, few milieus stand the test of time in the way the wonderful, whimsical world of the Dying Earth has. It can be condensed to a simple premise—a planet about to expire—but exemplary execution, imagination and iteration made these stories something so much more; something elegant and indelible; something very, very special.

The many and various tales about this breathtaking place and its uniquely appealing people—and creatures—have enthralled generations, and inspired, in the erstwhile, innumerable imitations. Jack Vance basically remade the face of fantasy fiction in one fell swoop with these books, and as The Guiding Nose of Ulfänt Bander?z shows, there’s a proliferation of life left in the Dying Earth yet.

Then again, the world is still ending. And this time, those who use magic are being blamed… quite rightly, as it transpires!

The people, both human and otherwise, reacted as people always have during such hard time in the immemorial history of the Dying Earth and the Earth of the Yellow Sun before it; they sought out scapegoats to hound and pound and kill. In this case, the heaviest opprobrium fell upon magicians, sorcerers, warlocks, the few witches still suffered to live by the smug male majority, and other practitioners of the thaumaturgical trade. Mobs attacked the magicians’ manses and conclaves; the servants of sorcerers were torn limb from limb when they went into town to buy vegetables or wine; to utter a spell in public brought instant pursuit by peasants armed with torches, pitchforks, and charmless swords and pikes left over from old wars and earlier pogroms.

Such a downturn in popularity was nothing new for the weary world’s makers of magic, all of whom had managed to exist for many normal human lifetimes and longer […] but this time the prejudice did not quickly fade.

Shrue the diabolist is “more sanguine than most” about this mad panic, but he still takes steps to escape the reach of the people. He sinks “his lovely manse of many rooms” into the surface of the earth, along with almost all of his equipment, his precious possessions, and twelve of his thirteen servants. With only Old Blind Bommp and KidriK—a gargantuan daihak whose binding would be the life’s work of a less long-lived entity than he—Shrue quietly retires to his polar cottage to wait out the witch-hunt… and perhaps, if the pogrom goes on long enough, the end of everything; a prospect he rather relishes.

Alas, his peaceful, pre-apocalypse retreat is interrupted when a harvested sparling heart brings news of an unexpected death:

Other magicians had suspected Ulfänt Bander?z as being the oldest among them—truly the oldest magus on the Dying Earth. But for millennia stacked upon millennia, as long as any living wizard could remember and longer, Ulfänt Bander?z’s only contribution to their field was his maintenance of the legendary Ultimate Library and Final Compendium of Thaumaturgical Lore from the Grand Motholam and earlier. The tens of thousands of huge, ancient books and lesser collections of magical tapestries, deep-viewers, talking discs, and other ancient media constituted the single greatest gathering of magical lore left in the lesser world of the Dying Earth.

Visitors, however, are rarely granted entry, and even then, “some sort of curse or spell on every item in the Ultimate Library” inexplicably inhibits the understanding of anyone other than Ulfänt Bander?z and his select apprentices… several of whom Shrue will meet when he takes it upon himself to explore Bander?z’s booby-trapped collection.

Booby traps aren’t the extent of what our diabolist and his cadre of companions will contend with, of course. After all, Shrue isn’t the only only magician with an interest in the lore Bander?z kept under elaborate lock and key. Enter Faucelme and his pet elementals, including two Purples and one incredibly powerful Red. These alone would be more than a match for KidriK… and they are not alone. Not at all.

“And thus began what Shrue would later realize were—incredibly, almost incomprehensibly—the happiest three weeks of his life.” It is Shrue who voices this thought, but I can only imagine Dan Simmons is speaking for himself here, equally, because this story must have been a blast to write; at the very least, it’s an absolute treat to read. I only wish it had lasted for three weeks.

Regrettably, The Guiding Nose of Ulfänt Bander?z is only the length of a novella, and though Simmons summons wonders enough over its extraordinary course to justify a markedly more substantial narrative, we must recall that this is a tale—however great—taken from the pages of the terrific 2009 tribute anthology Songs of The Dying Earth.

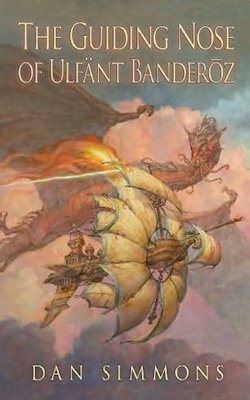

I’m perfectly pleased that the mighty minds behind Subterranean Press have broken it out into this beautiful, exclusive edition, with occasional illustrations by the World Fantasy Award-winning artist Tom Kidd. Indeed, I’d have dearly appreciated many more of these, given how gorgeous the cover and several small pieces decorating the interior are. Without any other added value—annotations, for instance, or a bonus story—I’m afraid this deluxe repackaging of The Guiding Nose of Ulfänt Bander?z feels more like a collector’s item than a opportunity for more readers to find and promptly fall for this fantastic homage.

Yet it is homage of the highest order. Simmons’ prose is moreish in much the same way as Vance’s words were in the originating stories. His vivid vision of the Dying Earth is as affectionate as any other I can recall, striking precisely the right balance between the playful and the profound. The Guiding Nose of Ulfänt Bander?z was by a large margin the most absorbing story in the landmark aforementioned anthology—despite it featuring fiction from literary luminaries like George R. R. Martin, Neil Gaiman, Jeff VanderMeer and Tad Williams, alongside an assortment of other awesome authors—and it has lost none of its power in the years since Songs of the Dying Earth.

It’s rather staggering that in excess of half a century since its creation, the Dying Earth is not just alive, but thriving. Yet it is. The Guiding Nose of Ulfänt Bander?z is all the evidence there needs be of that remarkable fact.

If “the memory of Jack Vance’s expansive, easy, powerful, dry, generous style, the cascades of indelible images leavened by the drollest of dialogue, all combined with the sure and certain lilt of language used to the limits of its imaginative powers” sounds good to you, then The Guiding Nose of Ulfänt Bander?z is sure to see you through.

And say you haven’t read the classic Vance… now’s your chance!

The Guiding Nose of Ulfänt Bander?z is published by Subterranean Press. It is available June 30.

Niall Alexander is an erstwhile English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com, where he contributes a weekly column concerned with news and new releases in the UK called the British Genre Fiction Focus, and co-curates the Short Fiction Spotlight. On rare occasion he’s been seen to tweet about books, too.